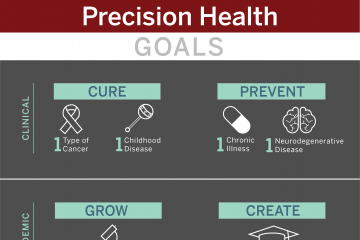

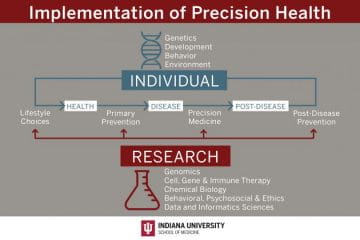

The Precision Health Initiative includes six fundamental pillars critical to the successful design and implementation of precision health. There are five selected clinical areas that build upon strengths of Indiana University and provide the opportunity to develop innovative research programs to support the implementation of transformative precision health for the state of Indiana. The $120 million Precision Health Initiative investment has generated substantial impact within the research, clinical and educational missions and the infrastructure that has been built will continue to drive further innovation and impact.

The multi-disciplinary team of researchers and clinicians that make up the IU Precision Health Initiative spans faculty expertise across IU School of Medicine, IU Bloomington and IUPUI. The initiative is led by principal investigator Tatiana Foroud, PhD, IU School of Medicine executive associate dean for research affairs and IU associate vice president for research and clinical affairs.